The file is one of the most basic and essential tools found in the jewelers bench. The proper file can rough out a shape rapidly or refine and smooth the finest of details. Having a good selection of files will enhance your creative potential. While files seem common, they are actually quite amazing tools with a long history.

The first files were made completely by hand with each tooth formed by striking a chisel at the proper angle and interval. This is how they were made for centuries. With the arrival of the industrial revolution, The first successful file cutting machines came into use in the mid eighteenth century. This, along with improvements in the refining of iron ore into steel and better heat treating processes, led to the development of the modern files.

Eventually standards were recognized as the industry of file production grew. Now, there is a plethora of standards. That brings me to the reason for this post. I will try to make it easier for you, the new jeweler, to wade through the ocean of terms and variations of what will work with jewelry.

Understanding how to choose the appropriate file sizes, shapes and styles of files for the work you do will help ensure high-quality, repeatable results for all your jewelry designs.

A file is a tool that is defined as a cutting tool as the teeth shave and cut small slivers of materials from the surface the file has been applied too. The most common file is a hand tool–a hardened steel bar with a series of sharp, parallel ridges, called teeth. To use a file, you want to choose a file shape that is as close a match as possible to the contour of the piece you’re filing.

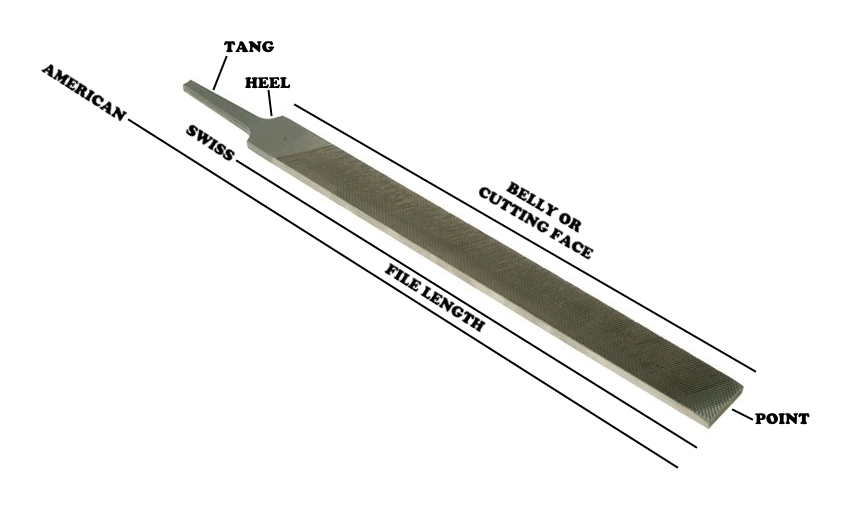

I am beginning with a simple drawing of a file and the named parts so the following discussion makes sense.

File Terminology:

Tang: The pointed end that goes into a file handle. If the file has a handle as part of the file design, this is known as a farmers file.

belly (face): The wide part of the file where the teeth are located. Also called the “cutting face”. Some files can feature different tooth patterns on each face.

File Length: For Swiss files, this is the length from the point to the heel. In American files, this also includes the tang.

Point: Opposite the tang is the front point of the file. Strangely enough,This is a misnomer as the point is often quite square and rarely pointed. Yet the point is, in fact, the end you point at the work.

Heel: The part of the file closest to the tang. It will not have teeth cut into this section. This is where the body of the file begins.

Not labeled:

Back: The convex side of a half-round or other similarly shaped file.

Edge and Safe Edge: The side surfaces of a file. this edge may be single cut as a very narrow file, or may be mirror polished as a safety edge.

Straight file: The profile of the file. both sides are parallel to each other.

Tapered File: The sides of the file taper for all or part of the length of the file.

Understanding the Cut #

This can be a very complex subject. So here is how I explain file cuts to those who visit my studio. Please note I will not be discussing files as they relate to wood or files for aluminum. I will be discussing files as they relate to being used to make jewelry.

Most hand files are classified as either “Swiss Pattern” or “American Pattern” (While there are also “German Pattern”, “French Pattern”, and “Metric” file systems as well, but as those are not as common as either Swiss or American, I will not be discussing those.)

American Pattern files

As a jeweler, you will not use many American Pattern files. While they can be as small as the files you will use for jewelry, in my experience, I have never seen a needle, escapement or riffler file that was not a Swiss pattern. I have a few that I use for large items, but these files tend to be 6 inches or larger. You may have a few for filing very large items so below is a description of how they are graded that I found on the internet.

“American Pattern files are available in three grades of cut: Bastard, Second Cut and Smooth. The length of a file also affects the coarseness, regardless of the cut. For example a 6″ Bastard Cut is a lot finer than a 12″ Bastard Cut. This is because shorter files are generally used for finer work. Overall, the finest would be a 4″ Smooth file and the coarsest would be a 16″ Bastard file. The relationship between the grades of coarseness for each length remains the same.”

Honestly, I find this confusing but as I only have a few in my shop, I just pick the file I want to use by eyeballing the teeth and deciding what works best.

Swiss Pattern Files

These are the files you will use for the vast majority of your work with jewelry.

Files are graded by a cut # ranging from 00 (the coarsest) to 6 (the finest). The cut # refers to the number of teeth per inch on the file. A file with a cut # of 00 has 38 teeth per inch. A file with a cut # of 6 has 173 teeth per inch. The list below I believe is reasonably accurate, but I did find some differences in my research for this blog post.

Swiss – 000 Coarsest of the Swiss pattern files. Swiss 000 cut files typically have 9 to 16 teeth/cm depending on the length and file type.

Swiss – 00 Second coarsest of the Swiss pattern files. Swiss 00 cut files typically have 12 to 20 teeth/cm depending on length and file type.

Swiss – 0 Third coarsest of the Swiss pattern files. Swiss 0 cut files typically have 16 to 25 teeth/cm depending on length and file type.

Swiss – 1 Fourth coarsest of the Swiss pattern files. Swiss 1 cut files typically have 20 to 31 teeth/cm depending on length and file type.

Swiss – 2 5th in smoothness of the Swiss pattern files. Swiss 2 cut files typically have 25 to 38 teeth/cm depending on length and file type.

Swiss – 3 Sixth in smoothness of the Swiss pattern files. Swiss 3 cut files typically have 31 to 46 teeth/cm depending on length and file type.

Swiss – 4 Fifth in smoothness of the Swiss pattern files. Swiss 4 cut files typically have 38 to 56 teeth/cm depending on length and file type.

Swiss – 5 Fourth in smoothness of the Swiss pattern files. Swiss 5 cut files typically have 46 to 68 teeth/cm depending on length and file type.

Swiss – 6 Third in smoothness of the Swiss pattern files. Swiss 6 cut files typically have 56 to 84 teeth/cm depending on length and file type.

Swiss – 7 Second in smoothness of the Swiss pattern files. Swiss 7 cut files typically have 100 teeth/cm.

Swiss – 8 Smoothest of the Swiss pattern files. Swiss 8 cut files typically have 116 teeth/cm.

Many of the smaller files you use will be be three to 5 inches long. These should lay on your bench on a piece of paper toweling to keep them from rolling into each other. These will normally not need handles.

If your file is large enough to have a handle, you should put one on. The tang is designed to be in a handle and it only takes one time of catching your file on something and driving the tang into your palm to discover the wisdom of having a handle. I also file the end of the handle flat so I can mark it with the profile and cut. This way it makes it easy to grab the right file without needing to search.

Files are cutting tools classified according to the following factors

1. The cut and spacing of the teeth on the file.

2. The shape and form of the cross section of the file.

3. The length of the file.

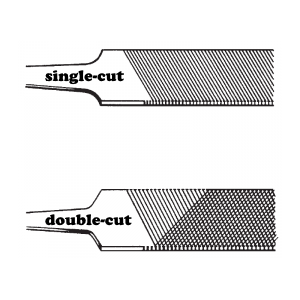

Cut and spacing of teeth on the file

The teeth on a file may be of single cut or double cut. A single cut file will be having parallel teeth and also known as flat file. Double cut file have two times cut-teeth. One set similar to those of a single cut file at about 60°, and the other running diagonally across making an angle of about 80° to the center line.

The spacing between teeth is known as the pitch and that has importance in the performance of the file. That is very technical and is not very important for jewelers with the exception of Checkering (texturing) files. But it might be important to someone so I am including it.

The shape and form of the cross section of file

Files are also grouped according to the cross section of them. Different cross section are required for shaping the contours of different forms. For example, a round hole can be shaped only by a round file. The type of files that are generally used for jewelry work are:

Needle Files:

Needle files are approximately 4″ to 5″ long and 3/16″ wide. Needle files are usually sold in sets of different shapes, packaged in a soft pouch, both for ease of handling and protection of the cutting teeth. These small files are used in applications where the surface finish takes priority over metal removal rates and they are most suited for smaller work pieces. You will eventually collect these in many shapes, sizes, and cuts.

Flat file

This file has parallel edges for about 2/3 rd of the length and then it tapers in width and thickness. The faces are double cut and the edges are single cut. two or three of these in different cuts will work for most of your work.

Hand file:

For a hand file the width is constant throughout the length but the thickness tapers as given in the flat file. In my experience, both faces are normally double cut and one of the thin edges will be single cut. The remaining edge is kept uncut in order to use for filing a right angled corner on one side only. this should be polished as a safety edge. These files are sold individually but you can also get them in sets that contain the most popular styles. Hand files are used for the removal of material from the work piece for shaping, smoothing or finishing. A couple of these in different cuts will be what you end up using a lot.

Riffler Files:

Riffler files are small to medium sized files (generally approximately 6″ long) manufactured in an assortment of cross sectional shapes and profiles. The varying profiles and shapes enable them to be used in hard to reach, or unusually shaped areas. They are often used as an intermediate step in die-making where the surface finish of a cavity die may need to be improved. Smaller and shorter versions that are about 4 inches long are used for jewelry.

Diamond Files:

Instead of having their teeth cut into the surface of the file, diamond files have small particles of industrial diamonds embedded in their surface (or into a softer material that is then bonded to the underlying surface of the file). The use of diamonds in this manner allows the file to be used effectively on extremely fragile materials such as stone or glass or very hard metals such as hardened steel or carbide (against which a standard steel file is ineffective).

Effective length of files

The size of a file is its effective length. The distance from the point to heal (excluding the tang) is considered as the effective length of a file. The length of file used for heavy works varies from 200 to 450 mm, while that for medium works varies from 150 mm to 250 mm. the fine work are done by files having length 100 to 150 mm.

File shapes and how they are used.

Flat:

Teeth on both flat sides and one edge, one edge is smooth. Slightly tapered in thickness. Use for finishing flat surfaces.

Thin warding (entering):

Teeth on both flat sides and both edges. Tapers to a point. Use for hard-to-reach areas and for making notches.

Half round file:

In half round file one side is flat while the other side a portion of a circle. The flat side of the file is always double cut, while the curved surface is normally single cut. Use for filing flat and curved surfaces, corners, and the inside of larger rings.

Half-round ring:

This is like the file listed above, but will normally be large enough to need a file handle. It will have teeth on both sides. Tapers to a point with one flat and one low-domed side. Use for filing flat and curved surfaces, excellent for filing inside ring shanks. I have several of these in different cuts and diameters to match the most common ring sizes.

Round (rat-tail):

Teeth all around, narrow diameter. These will taper slightly if you buy them from a jewelry tool supplier. Use these for enlarging holes or cleaning out tubing and other round metal. For a larger size that works the best, go to your local hardware store and pick a couple of sets of files meant for sharpening chainsaw blades. these will not taper. With care, these will last decades. I am still using a set that I purchased in the early 1990s and they are as sharp as when I bought them.

Three-square (triangle):

Teeth on three flat sides (also called a triangle file). For filing point prongs on marquise- or pear-cut settings, and sharp angles or creases in metal. For filing corners of angles less than 90° triangular files are used. The three faces are normally double cut. I will often polish one face as a safety edge for working around bezels and prongs.

Square:

Teeth on all four sides, Most often these will have a slight taper. Use for filing flat, straight angles. these work great for filing corners and slots.

Crossing (double half-round):

These have teeth on both sides and are shaped like a double half-round. Two low-dome, half-round areas will be back to back for filing curved surfaces such as inside of fine work where you need to match a very small curve.

Barrette:

Vaguely triangular shaped. The teeth are on the broad flat side only while the edges taper inward and the file tapers to a point. The smooth, narrow side prevents removal of metal from adjacent surfaces. You should polish the edges to a mirror finish as a safety edge.

Checkering (texturing):

Checkering files are parallel in width and may be gently tapered in thickness. They have teeth cut in a precise grid pattern for making serrations and doing checkering work.The teeth will be on the two flat sides with smooth parallel edges (polish these). Used to put decorative serrations on the edge of a bezel, create a Florentine finish by hand and quickly remove metal. You can order these in different cuts to match the most common florentine texturing line engravers.

The proper use of your files

Filing is an art. It’s not just rubbing the file back and forth. Every stroke should count and move you one step closer to a smooth, polished finish without gouges or abrasion marks. Take your time, practice, and watch carefully as you work. practice with intent and you will learn to file with ease. For me, this is almost a meditative task.

The file being used should have your the forefinger placed on top of the handle in line with the file. For normal flat filing, the file should be moved forward on an almost straight line of a single plane, changing its course only enough to prevent grooving.On the reverse stroke, it is best to lift the file clear of the work piece, except on very soft metals. Even then, the pressure should be very light – never more than the weight of the file itself. When there is a great deal of heavy filing, it is better to have the work slightly lower. If the work is of a fine and delicate nature, the work can be raised to eye level on your bench pin.

To prevent the teeth from becoming clogged as you work, tap the end of the file lightly on the bench after several strokes to dislodge chips of material from the teeth. Clean your files occasionally with a file brush. To clean, hold the file at the tang end with the point of the tang resting on the work surface and rub the brush diagonally across the file.

There are three main filing techniques and as a jeweler you will use two of them everyday.

Straight filing:

Files have forward-facing cutting teeth, and cut most effectively when pushed straight ahead over the work piece. Straight filing is pushing the file lengthwise down the work piece in a straight or slightly diagonal position. The cutting stroke is the push stroke. Done correctly, the return stroke shouldn’t touch the work piece. Straight filing can deliver maximum material removal or smooth final finish. Sometimes, the shape of the material can make straight filing difficult or awkward.

Draw filing:

Draw-filing involves laying the file sideways on the work and carefully pushing or pulling it across the work. This catches the teeth of the file sideways instead of head on, and a very fine shaving action is produced. There are also varying strokes that produce a combination of the straight-ahead stroke and the draw-filing stroke, and very fine work can be achieved in this fashion. Using a combination of strokes, and progressively finer files, a skilled operator can attain a surface that is perfectly flat with a nearly mirror-finish.

Lathe filing:

The third technique is lathe filing and, just as its name implies, is the process of stroking the file against a work piece that is revolving in a lathe or hand piece. This can be useful when truing a work piece or for removing material. As with any application involving your hands and face, and revolving tools, lathe filing requires with much care and attention. You will not use this method very often, but you need to know about it.

Filing Different Metals

Because different metals vary greatly in properties, consider the nature of the metal you’re working with when choosing the right file for the job. Soft, ductile metals require a keen edge and light pressure. Harder materials require duller teeth and more pressure.

One safety note: Wear a Respirator! Soft materials such as silver, brass, and copper present distinct filing conditions.

Keep the pressure off. Apply only enough pressure to allow the file to do the work. Feel the teeth biting into the work piece. Your movement should be fluid and smooth. Applying the correct pressure will also result in the fastest removal of material, even if it takes a few more strokes to get the job done.

Filing silver and its alloys

Fine silver files easily and care should be taken to not groove it with your files accidentally. I can quickly clog your files so make sure to only use a light pressure. Sterling silver is harder and as such, use a light to medium pressure. Coin and German silver in my experience files like annealed brass.

Filing gold and its alloys

Many alloys are quite hard and need a moderate pressure to file them. The lower the gold content, the more pressure you need. As the gold karat goes up, it becomes easier to file. Due to the denseness of the metal you want to use a lighter touch, but you will find it files very smoothly. 18 karat and up is a dream to file.

Filing Platinum group metals

Pure platinum and its alloys with other platinum group metals such as palladium, ruthenium, rhodium, iridium and osmium are varying densities. One thing they all have in common is how smoothly they file. A light touch is needed as the metal is fairly dense. it is easy to clg your files. I suggest keeping a separate set of files just for platinum. Bits of gold and silver can give you headaches when soldering later. keep everything spotlessly clean when working with this. I love working with these metals and high karat golds.

Filing Brass

Brass is difficult because it’s softer than steel, but tougher and harder than aluminum. Filing brass requires a sharp file with sturdy teeth and a cut that prevents grooving and running. Use a specifically designed brass file, and apply moderate pressure.

Filing Bronze

Similar to brass but dependent on the content of alloying elements. Cross the direction of the cutting stroke to avoid grooving. it can feel gritty. be prepared to have your files skip.

Filing amber and Plastics

Amber and plastic requires a file with high, sharp teeth. Soft materials are filed in shreds, so a wide tooth file should be used for rough shaping, then a very fine toothed file for the fine shaping.

file care

There are a number of simple steps you can take to ensure your files last a long time.

The teeth of the file should be protected when the file is not in use by hanging it on a rack or keeping it in a drawer with wooden divisions. Files should always be kept clear of water or grease, since this impairs the filing action. It is advisable to wrap the file in a cloth for protection when it is carried in a toolbox.

Protect the teeth. Tossing your files in with all your metal tools is not a good idea! Ideally, hang them up or keep them in a drawer with non-metallic dividers and enough room to fit without a lot of contact. Store them away from water, dirt, grease and filings.

The file teeth should be kept clean at all times by using a file card, or a wire file brush, to clear the grooves between the teeth.

A file should never be used without a tight fitting handle. Serious accidents can result if the handle becomes detached exposing the sharp point of the tang.

Keep it clean and clear. Get a file card and use it while you file and after you’re done. A file card has rows of small, stiff wire that cleans debris from a file’s teeth. Remember that filing creates heat and filings are sharp. Cleaning your file by hand is one way to pick up a metal sliver. Instead, use a file card, which clears away filings before they get stuck in the file—or in your finger.

I hope this helps you. If you have any questions, feel free to post a comment.