Practice makes perfect *, (* but only if you do it right.)

Originally posted on July 16, 2019 by Gerald A. Livings

Question: “How do you get to Carnegie Hall?”

Answer: “Practice, Practice, Practice.”

This old vaudeville joke about Carnegie Hall, which opened in 1891, has been around so long, that no one knows who first said it. Made famous by Jack Benny (1894-1974), the vaudeville, radio and television comedian, it is probably the most quoted guidance on the importance of practice in order to learn a skill.

This quote is about music and musicians, not jewelry, but it has become the default advice on how to learn just about anything.

Unfortunately, it is probably the worst advice you can give someone to help them master any skill.

So how does this tie into learning metal arts as they relate to jewelry? let me begin by repeating what I tell everyone who comes over to my shop to learn.

“I want you to learn the right way to make jewelry by learning the right habits. I do not want you to struggle like I do because I did not know how to deliberately learn.

Because unlearning a bad habit is much harder then trying to learn a good habit in the first place.

The title of this post is “Practice makes perfect *, (* but only if you do it right.)”. Which is correct “If you do it right”. I hope with this post to share what I consider “The right way” that I learned the hard way.

Some background on my experience: I started making jewelry as a hobby in 1985 while I was in the Army. A few friends helped me get started, and after I left the Army, I continued on my own. reading everything I could find. I blindly worked on making jewelry without practicing making jewelry.

It wasn’t long before I started running into problems that I did not know how to fix because I did not understand what was wrong.

It was a long time before I began to understand that the problem was that I did not know that I was the problem.

I had taught myself the wrong way to do different processes and as soon as I identified the problem, I had some hard thinking about what to do to fix it. This lead me to think about the nature of how to practice and learn. I found that I had spent many years learning the wrong way to do what I do.

It did not take long to learn that changing a bad habit is much harder then trying to learn a good habit in the first place. So I needed to practice. But how? What I had done before caused my failures. So I figured out that I had to learn how to learn. I had to learn how to practice. So thus began my search to learn how to learn. It did not take long to discover that for the skills I needed, I had to learn how to deliberately practice the correct movements so those could become ingrained as the correct way to do each process.

So how does “practice” fit into learning?

It does not matter what skill you are learning, practicing the right way can mean the difference between good and great.

The fact that we practice something means that it is a deliberate action. “to do something repeatedly in order to master it” or “to pursue as an occupation or art.”.

What works best? Just practicing is not the answer. Is perfect practice what you need or will bad practice make you better? I have heard many people say “practice until you get it right”. I have also heard many people say “practice until you can’t get it wrong”. So what works the best to efficiently learn and master a skill? It is true that there are no shortcuts to mastering a skill, but there are certainly ways of needlessly prolonging the learning curve. I am pretty sure I figured out all of those at one time or the other! I wasted many hundreds of hours because nobody ever taught me the most effective and efficient way to practice.

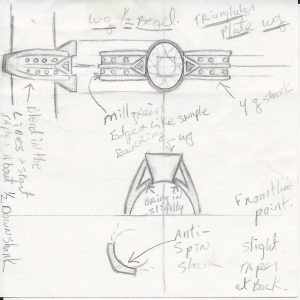

You need to start with a pad of paper and a pencil. Your first and most important tool as a jeweler. is a pencil. Use it and take notes, and make a list of what skills you need to learn. This is important because if you do not know what to learn, you will become frustrated and give up. I was given this advice when I started, but did not take it to heart. It took another friend to remind me of this and since then, I have had an easier time learning.

Now we have reached the point where I give you my take on how to practice. After many years, I do what I have come to describe as “Deliberate Practice”.

I like to think of this as three steps.

- Consistency

- Evaluation

- Repetition

1. Consistency

Consistency is the first step and requires patience and perseverance to develop. At first, this is frustrating because when starting, a consistent quality of work is almost impossible to achieve. But with patience and perseverance, consistency in workmanship begins to happen.

It took a while to discover that I was trying to learn too many processes at once and all of the subtle nuances of each process were lost in the jumbled pile of minutia. Not in the sense of trivial details, but the small, precise details. The details I did not have the experience to know how to see. It took me a while to learn that the best way to learn was to be consistent with one process, practice that, evaluate, and practice some more. Then repeat until I have it down without thinking about it.

2. Evaluation

To best learn, you have to objectively look at your own work and learn to be a perfectionist. Every time you complete a process ask yourself these questions. Was this done correctly? If yes, question 2: Was it easy?

If both of those questions are “Yes”, you have successfully learned a skill. it may take hours, days, weeks or months before you can say yes to both of these questions. More than likely the answer is no and you need to evaluate your work. You will need to break down every step of what you have been practicing and check your emotions and attitude at the door before you begin.

I found this really hard when I started. I did not know enough on my own to be able to evaluate how I was doing. This is where a teacher would have helped a lot. I did not know that at the time. And I did not understand the process of education enough to know that I was unable to properly evaluate my own work.

How to evaluate my own work was, and still is, the hardest part of learning how to learn. At first it took some time to discover that to be honest with myself was extremely hard. Either I looked at something and thought “Good enough”, or I picked it apart as garbage no matter how well I had done. it is a hard task to critique your own craftsmanship without emotional attachment. We, as artists always are always our own hardest critics. Every piece has a bit of our soul, sweat and tears in it. so to be reflective without being emotionally tied to our work is extremely hard to learn.

I found it easiest to assess my performance against written specifications. Remember that list I told you to make earlier? Pull that out. Now ask yourself the questions above and take notes. Make sketches, write down what went well and what did not. Put these notes into a notebook and/or a file. When you are critiquing your own work, be a perfectionist. Evaluation is very hard. But with practice, it gets easier and it will help you learn faster.

3. Repetition

This is what I call training your “Lizard Brain”. What is the lizard brain? For my purposes, it is the part of the brain that we have made changes to during skill learning. When you pick up a saw frame for the 30,000th time, this is where the information is kept that the brain sends out to the muscles in your hand, thereby changing the movements that are produced without you having to think about what to do.

Now for the tricky part about repetition. If you do it wrong, you will learn the wrong thing! So you need to find out what you should be doing. Start slowly practicing to get the movements correct. Then speed up a little bit. Take sawing a straight line in a piece of brass as an example. The kerf should be on one side of your scribed line, and should not deviate from that line more than half the width of the kerf for blades 0 and larger, for blades 1/0 and smaller, the width of the kerf. The cut should be flat and straight. The tooth marks should be even when you look at the cut metal. These are all separate skills to learn. Start by just learning how to keep your blade next to your scribed line. Practice that. evaluate how you did, and practice again. When you can consistently keep your blade next to your scribed line, start practicing making your cut straight. The metal of the cut should be at a 90 degree angle to the surface of the metal sheet.

See where I am going with this? Break down each skill into the little parts, and practice each part. This is “Deliberate Practice”.

Even the simplest everyday actions involve a complex sequence of tensing and relaxing many different muscles. For most of these actions we have had repeated practice over our lifetime, meaning that these actions can be performed faster, more smoothly and more accurately. Over time, with continual practice, actions as complicated as riding a bike, sawing a straight line, setting a diamond into a ring, or even playing a tune on a musical instrument, can be performed almost automatically and without thought.

See that link above about “Unlearning a bad habit is much harder then trying to learn a good habit in the first place”? Click on it, print it out and put it in your binder as the cover. This is where your evaluation comes in handy and breaking your practice down into single processes. This is something I still struggle with after 30 plus years. It is really hard to retrain yourself out of bad habits.

Some last thoughts…

While some people are able to learn with a minimal effort, this is the exception. The vast majority of successful jewelers achieve their success by developing and applying “Deliberate Practice”. If you want to become a successful jeweler, don’t get discouraged, don’t give up, just work to develop deliberate practice habits and you will find that your skills and your knowledge increase. As your your skills and your knowledge increase. you will find that your ability to learn and evaluate your own work improve as well.

Here are the things I found that I was doing wrong and were stopping me from being deliberate in my practice.

1. I tried to cram all my practice into one session.

I would find myself staying up late at night expending more energy trying to keep my eyelids open than practicing. I would try to get a certain number of hours of practice in each week and if I was not able to break it up, I would cram my practice into marathon sessions that did more harm than good. I learned to space my practice out over shorter periods of time of about 2 hours per session. So for you, please know that you need to learn to be consistent in your studies and to have regular, yet shorter, deliberate practice sessions.

2. I would not plan what I was going to study.

This goes back to the advice above about making a list. At first I would sit at my kitchen table with the intent to practice, but would dither and start a couple of things, then become frustrated and quit. It took the advice of a friend to remind me that I needed to make a list of skills to practice. With this, I could sit down with the intent to practice one skill. Believe me, this helps more than you know. So make a list. It may take you years to get to the end as you will keep adding to it, but that is part of being consistent.

3. I did not study at the same time.

I would fit in my practice at odd times and I found it hard to consistently sit down and learn. Not only is it important that you plan when and what you’re going to study, it’s important you create a consistent, weekly study routine. When you study at the same time each day and each week, you’re studying will become a regular part of your life. If you have to change your schedule from time to time due to unexpected events, that’s okay, but get back on your routine as soon as the event has passed.

4. I would stop if I made a mistake or was having a hard time.

When I made a mistake, I would beat myself up over it and just stop. Sometimes it would be days before I could force my stupid self to continue.

Yeah. It was that bad. So take it from me. Do not beat yourself up over a mistake. This is why we practice. Keep going if you make a mistake. Even the most experienced jeweler who is consistent and well-organized with the way they practice slip up sometimes. Plan for potential failure, and don’t beat yourself up if you make a mistake along the way.

So this brings us back around to “Practice makes perfect *”, (* but only if you do it right.)

I hope that you can learn a bit from my own failures, and my successes. And as always, comments are welcome below.